Planning Long Distance Outings

Part 2 - Groups, Gear, and Gettin' There

To me, the single most important factor to consider when you start conceptualizing a trip into the wilderness is that the skills and personalities of the participants (including yourself) should be matched to the difficulty of the trip. Above, we discussed how to go about finding the best place for you to go on your wilderness expedition and some thoughts on what might make for effective route planning. This month, I wanted to share with you some my experiences concerning choosing people to accompany me on trips, working out logistical details for getting to the trailhead, even though it may be 2500 miles away, and what you should think about when it comes to equipment for a long trip. First, people.

There are at least four major aspects of choosing the right kind of folks to accompany you on your vacation: Who you want to be with, what kind of backcountry experience they have, the degree of independence they exhibit, and their personality quirks. First, it may sound pretty self evident, but I think it's always a good idea to limit your initial thoughts to only those people that you like being with. Not everyone will agree with me,  but I think that you radically increase your chances of a successful trip if you go with your friends, and not just acquaintances, or the friend of a friend of a friend who heard about your trip. The more you know about someone, the more accurate a prediction you can make about how they'll do in the wilderness. If you don't know them, it's a total crap shoot. I can think of a number of trips (fortunately, none were mine) that have broken up largely because people weren't really friends. The new guy makes a pass at someone else's girlfriend, the gal who said in her letter that she was an experienced backpacker, but that was 10 years ago and she's put on 40 pounds since then. There's another aspect that most of us don't like to think about, and that's probably because it sounds a little cold: In the wilderness, there's always a finite risk that someone will do something stupid and either hurt themselves or someone else. This may result in an aborted trip. I wouldn't like it, but I can much more easily forgive a friend than I could someone I hardly know.

but I think that you radically increase your chances of a successful trip if you go with your friends, and not just acquaintances, or the friend of a friend of a friend who heard about your trip. The more you know about someone, the more accurate a prediction you can make about how they'll do in the wilderness. If you don't know them, it's a total crap shoot. I can think of a number of trips (fortunately, none were mine) that have broken up largely because people weren't really friends. The new guy makes a pass at someone else's girlfriend, the gal who said in her letter that she was an experienced backpacker, but that was 10 years ago and she's put on 40 pounds since then. There's another aspect that most of us don't like to think about, and that's probably because it sounds a little cold: In the wilderness, there's always a finite risk that someone will do something stupid and either hurt themselves or someone else. This may result in an aborted trip. I wouldn't like it, but I can much more easily forgive a friend than I could someone I hardly know.

Secondly, consider the back country experience and skills of those people that you might want to have along. I don't care if your new boyfriend is both a hunk and really sensitive. If he's never backpacked before, this is probably not the year to take him with your fiends on a seven day cross-country traverse along the Sierra High Route in the John Muir Wilderness . Obviously, this doesn't mean that no one who hasn't been on a long trip out west should come with you on this trip. After all, we all are virgins one time. But at least think about how these folks hike. If you want to spend most of your time fishing and photographing, is your good buddy who's used to covering 18 miles per day really gonna be happy covering 25 miles in a week with three layover days? If the trip will involve a lot of cross country route finding, your friend who may be a strong hiker but who can't read a compass or a topo map may become a problem, especially if he or she gets separated from the main group. If the route will cross glaciers, does everyone know how to walk with crampons and a rope, and how to perform crevasse rescue? Your life may depend on their skills.

. Obviously, this doesn't mean that no one who hasn't been on a long trip out west should come with you on this trip. After all, we all are virgins one time. But at least think about how these folks hike. If you want to spend most of your time fishing and photographing, is your good buddy who's used to covering 18 miles per day really gonna be happy covering 25 miles in a week with three layover days? If the trip will involve a lot of cross country route finding, your friend who may be a strong hiker but who can't read a compass or a topo map may become a problem, especially if he or she gets separated from the main group. If the route will cross glaciers, does everyone know how to walk with crampons and a rope, and how to perform crevasse rescue? Your life may depend on their skills.

Third, consider the independence level of your candidate hiking buddies.  Are they inherently leaders, followers, or just cantankerous independent types? Personally, I prefer to have independent types with me. I don't really want to be a leader, I just like to coordinate the planning of the trip (that's so we go where I want to go). Well, if I don't want to lead people, then I surely don't want to have people with me who want to be led. If you like to lead people, or are at least comfortable in that role, then you'll be happy with a group of followers. That's great. I just hate to have to be worrying about someone when they're on a trip with me. I like to feel as though everyone would get along just fine without me, except for missing someone to harass. And try to keep in mind that, no matter how well lead or coordinated a trip you take, ultimately, everyone is responsible for themselves. The wilderness accepts no excuses.

Are they inherently leaders, followers, or just cantankerous independent types? Personally, I prefer to have independent types with me. I don't really want to be a leader, I just like to coordinate the planning of the trip (that's so we go where I want to go). Well, if I don't want to lead people, then I surely don't want to have people with me who want to be led. If you like to lead people, or are at least comfortable in that role, then you'll be happy with a group of followers. That's great. I just hate to have to be worrying about someone when they're on a trip with me. I like to feel as though everyone would get along just fine without me, except for missing someone to harass. And try to keep in mind that, no matter how well lead or coordinated a trip you take, ultimately, everyone is responsible for themselves. The wilderness accepts no excuses.

Personality quirks can usually be amusing. Sometimes they get annoying, and more frequently than one would like, they can drive you nuts. This makes for a good reason why you should ideally know someone and yourself pretty well before you join with them for a week or so of wilderness adventure. For example, if you are the mother hen type (I admit I am a bit of one), and want all the chicks in the nest as it gets close to dark, then I can think of at least one of my friends that you may not want to have along with you. He habitually gets to camp with the rest of the crew, and then takes off heaven know's where, exploring, meditating, rock climbing, or whatever, only to show up when he feels like it, usually cooking his dinner in the dark. My wife, Susie, is a very strong backpacker, and could route find her way out of a maze. But please, don't let her see a mosquito. This otherwise extremely rational woman turns into a crazed, paranoid character with a mental age of about five. Not only does she go berzerk if she gets a bite, she goes crazy if someone else in the party allows themselves to get bitten. I've made a mental note never to suggest a trip into the Boundary Waters Canoe Area at the end of June.

Before we get to discussing the logistics of the trip itself, I'd like to make a few comments about the equipment that you take on a long trip, and share some of my true life stories. The bottom line to this will be that overnight, one can put up with almost anything. When, you're hung out about three days from the nearest trail head, it's a whole 'nother ball game. One thing I have learned from other folks and their problems is that you should know how your stove works, and CHECK IT OUT before you hit the trail. This  goes for all your equipment. My rule of thumb is that I never take a piece of equipment with me on a long trip that I haven't field tested first. I recall one time that a friend's husband bought her some "deluxe" straps with which to attach her sleeping bag to her pack the morning that she was leaving for a week long trip in a canyon. Guess which straps didn't hold when she put her bag on her pack at the trail head. Do you know - not memorize - the directions, but really understand - how your stove works. Can you repair it under field conditions? Have you checked the waterproofness of your tent or rain gear lately. I know that it may sound silly, but I've stood in the shower for 30 minutes with my rainsuit on, trying to find the source of a leak. (Of course, with the leaks plugged, this means that I will be dry under field conditions of standing perfectly still, in 71 degree rain. Fat chance.)

goes for all your equipment. My rule of thumb is that I never take a piece of equipment with me on a long trip that I haven't field tested first. I recall one time that a friend's husband bought her some "deluxe" straps with which to attach her sleeping bag to her pack the morning that she was leaving for a week long trip in a canyon. Guess which straps didn't hold when she put her bag on her pack at the trail head. Do you know - not memorize - the directions, but really understand - how your stove works. Can you repair it under field conditions? Have you checked the waterproofness of your tent or rain gear lately. I know that it may sound silly, but I've stood in the shower for 30 minutes with my rainsuit on, trying to find the source of a leak. (Of course, with the leaks plugged, this means that I will be dry under field conditions of standing perfectly still, in 71 degree rain. Fat chance.)

Always, always, always carry a few ounces of critical spare parts with you. I continue to learn hard lessons in this realm. For example, in 1985, my former wife, a friend, and I were hiking in the Beartooth Wilderness Montana. What do you think the chances would be of both my wife's and my flashlight bulbs burning out on the same night? I only had one spare bulb with me. Really stupid. I now carry four. I once lost the clevis pin which attached my hip belt to my pack frame. Had I not been carrying several spare pins and split rings, my hiking would have been miserable. And even well prepared backpackers sometimes forget that their camera is a piece of equipment. One friend of mine had her camera battery die on the second day of a trip. Fortunately, I had several spares, and was willing to sell her one for only $100. Not a bad deal. But another time, another friend had the battery on his Olympus OM-2 go dead. The rest of us didn't use the same battery, so guess who had only a few pictures of the trip. And hey, camera batteries (or clevis pins, or spare flashlight bulbs, or stove parts) aren't very heavy, and they can be worth their weight a long way from the trailhead. I once watched a friend of mine go through 3 new camera batteries in his pack before he found one that actually worked. A good idea is to go through your equipment ahead of time, figure out what could break or burn out, or whatever, and think about what you would do to fix it. A little time spent in the quiet of your home can pay big dividends on the trail.

I'd like to finish my discussion of the planning of long distance outings with some of the things that I've learned by making mistakes when it comes to travel logistics. Some of these may sound like incredibly picky details, but Murphy's Law usually functions just as well west of the Mississippi as it does to the east.

1. Make sure that you know if any special permits are required to travel in the area that you're headed. Some wilderness areas limit the party size, or the elevation above which you can't have a campfire, or what kind of hooks you can fish with, how close to water supplies you can set up camp. I usually check the website of the land management agency or call the backcountry rangers and ask them these and other questions before I finalize my route. And don't assume that you can just show up and hike where you want to. More and more wilderness areas require advance permits. As such, it is necessary to plan your trip to those places months in advance. For the two trips I took in 1998, I had to sign up on New Years Day for a May 2 start in the Grand Canyon, and March 1 for a late August start in California's John Muir Wilderness.

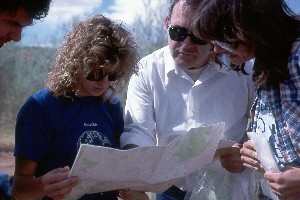

2. Make sure that everyone in the party has their own set of topo maps.  It may sound like overkill, but people can and do get separated from the main group. And to make sure that everyone is working with a complete set of information, I usually provide each individual with a set of copies of the trail or route descriptions from all the hiking guides that are available. To save weight, I make double sided copies.

It may sound like overkill, but people can and do get separated from the main group. And to make sure that everyone is working with a complete set of information, I usually provide each individual with a set of copies of the trail or route descriptions from all the hiking guides that are available. To save weight, I make double sided copies.

3. Believe it or not, it's best not to assume that everyone knows the way to the airport, or how much time it will take them to get there. While it might sound unnecessarily Big-Brotherish, if I'm coordinating the trip, I like to know where everyone will be the day that we leave, how they're planning on getting to the airport, and what time they plan to leave. This comes from learning this lesson the hard way: One time, I assumed that everyone could take care of themselves. Well, one of the guys didn't allow enough time to get from his job to the airport, and he missed the plane. It cost him big $ to take another flight, and screwed up the first part of everyone else's trip.

4. I think that it's best to let one person handle the airline reservations, ticket payments, van and motel reservations. That way, the travel agent only has to deal with one person. If you have individuals coming from different directions, make sure that you know what their itineraries are as well. And have contingency plans to cover late or canceled flights. If the group is traveling on more than one set of flights (I have dealt with as many as four sets simultaneously), it's a good idea to appoint someone back home (who will be near their phone) to act as a message clearing house. Despite recent advances in technology, it's still hard to get hold of someone when they're flying at 35,000 feet. And remember that you can request special meals on airline flights for your veggie or low-fat diet friends. And in these days of triple frequent flyer mileage if you were born in the new moon and your mother's aunt holds a gold Visa card, your friends may act a little cool toward you if you forget to include their frequent flyer numbers.

5. Make sure you have rented enough volume of van or autos to carry all the gear that your party will bring. I've found that 10 people will easily fill a 15-passenger van and a large car with all their stuff. It's not all that much fun to have to sit on your buddy's lap for 300 miles. When renting vehicles, cheapest is not always the best. I remember one time that we rented a van and a mid-size car in Las Vegas. The next morning, we noticed that the steel cord was coming through the treads of the car's front tires. We were eventually reimbursed for the new tires we had to buy, but nothing could replace the time that we squandered waiting for the tires to be changed in a Shell station in St. George, Utah.

6. Don't forget to check with the highway patrol or the AAA in the state to which you're headed before you leave you home base. Some highway trip planning software permit Internet-based updates. Rock slides, avalanches, and wash outs can often close 2-lane highways in the west for days at a time. Once, we had to drive nearly 150 miles out of our way because I forgot to check. I came in for alot of ribbing on that trip.

7. I can't emphasize enough the need to be realistic about the time required to get from the airport at the end of your flight, and your trailhead. My experiences have been that I usually land only to within 150 - 400 miles of the trailhead.  If we leave for a trip late Friday afternoon, that means we usually land out west somewhere around 11 pm body time (which, of course, may be only 8 or 9 pm local time). Next, we have to buy some Coleman fuel for our backpacking stoves (did you think to check for a grocery store or K-Mart that's open late that sells such fuel?). Then, we head for a grocery store, to buy lunch materials for the next day, because there aren't any McDonald's in the boon docks where we're headed. Of course, the more people on the trip, the more complicated the grocery shopping becomes. Invariably, just as we're ready to finally pull out of town and head for some motel 125 miles down the road, two members of the party have a fast food attack. One won't settle for anything but a Big Mac, while the other has to have a vegetarian Burrito Supreme at Taco Bell. When we pull into the motel, it's about 1 am local time, and the manager is so bleary eyed that he can't find our reservation. (Hint: call the motel when you land to let them know you're on your way. They may to give your room away if you don't show up by midnight.)

If we leave for a trip late Friday afternoon, that means we usually land out west somewhere around 11 pm body time (which, of course, may be only 8 or 9 pm local time). Next, we have to buy some Coleman fuel for our backpacking stoves (did you think to check for a grocery store or K-Mart that's open late that sells such fuel?). Then, we head for a grocery store, to buy lunch materials for the next day, because there aren't any McDonald's in the boon docks where we're headed. Of course, the more people on the trip, the more complicated the grocery shopping becomes. Invariably, just as we're ready to finally pull out of town and head for some motel 125 miles down the road, two members of the party have a fast food attack. One won't settle for anything but a Big Mac, while the other has to have a vegetarian Burrito Supreme at Taco Bell. When we pull into the motel, it's about 1 am local time, and the manager is so bleary eyed that he can't find our reservation. (Hint: call the motel when you land to let them know you're on your way. They may to give your room away if you don't show up by midnight.)

Planning the next day's drive to the trailhead can be tricky. What I usually do is find out what time it gets dark at the first night's campsite, add a one hour pad, and then start to work backwards to figure out what time every one has to get up at the motel. Remember that the more people you have in the party, the longer it will take. Usually, the trips I take are one way or open ended loops, both of which require a car shuttle. That can take anywhere from two to five or six hours. Continuing to work backwards, it will always take more time than what you think it ought to drive from motel to trailhead. If you are driving through particularly scenic country, people will want to stop to take pictures. Allow some time for that. Just as invariably as the night before, someone else will just have to get some Oreo cookies that we forgot to pick up at the grocery store the night before. Another 15 minutes. Even relieving yourselves can consume large chunks of time, as it did one year on the Navajo Reservation, when 12 of us had to use a one-holer. Allow time for breakfast in the morning, and don't forget that everyone will have to unpack their gear and pack it into their backpacks before they leave the motel, all while suffering from too little sleep and too much jet lag.

Planning the next day's drive to the trailhead can be tricky. What I usually do is find out what time it gets dark at the first night's campsite, add a one hour pad, and then start to work backwards to figure out what time every one has to get up at the motel. Remember that the more people you have in the party, the longer it will take. Usually, the trips I take are one way or open ended loops, both of which require a car shuttle. That can take anywhere from two to five or six hours. Continuing to work backwards, it will always take more time than what you think it ought to drive from motel to trailhead. If you are driving through particularly scenic country, people will want to stop to take pictures. Allow some time for that. Just as invariably as the night before, someone else will just have to get some Oreo cookies that we forgot to pick up at the grocery store the night before. Another 15 minutes. Even relieving yourselves can consume large chunks of time, as it did one year on the Navajo Reservation, when 12 of us had to use a one-holer. Allow time for breakfast in the morning, and don't forget that everyone will have to unpack their gear and pack it into their backpacks before they leave the motel, all while suffering from too little sleep and too much jet lag.

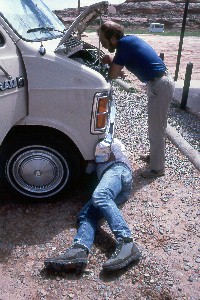

As I read what I've written, I realize that this sounds a little like "The Keystone Cops Meet the West," but truthfully, all of these things have happened to us, at one time or another. Of course, I haven't discussed the time when one of the vans developed a problem and Ray Payne had to overhaul the fuel system with a Swiss Army knife and a paper cup while we sat outside a general store in Mexican Water, Arizona. But that's good for another story. (Back to Part 1.)

© Roger A. Jenkins, 1988, 2000