Mapless in the Backcountry??

The Arguments For and Against Carrying Navigational

Aids

Recently,

my good buddy Will was leading a semi-exploratory backpacking trip for

the Knoxville Group of the Sierra Club in the Big Frog Wilderness in

extreme southeastern Tennessee. It was an interesting trip, in part

due to the storminess and the size of the hailstones which pounded

them as they arrived at a campsite. But the next day, things turned

more interesting, when five members of the party made a couple of

wrong turns, and ended up way off course. It turns out that none of

them had a map that could be really used for backcountry navigation

with them. (Full disclosure here: one of the parties had a map - back

in her car, so it is not like she did not intend to bring a map.)

Recently,

my good buddy Will was leading a semi-exploratory backpacking trip for

the Knoxville Group of the Sierra Club in the Big Frog Wilderness in

extreme southeastern Tennessee. It was an interesting trip, in part

due to the storminess and the size of the hailstones which pounded

them as they arrived at a campsite. But the next day, things turned

more interesting, when five members of the party made a couple of

wrong turns, and ended up way off course. It turns out that none of

them had a map that could be really used for backcountry navigation

with them. (Full disclosure here: one of the parties had a map - back

in her car, so it is not like she did not intend to bring a map.)

I have been mulling over the issue of who does and does not carry a map with them on backcountry outings - and why - for some time, and I guess this particular incident brought my thinking to a head. I had my own ideas why people behave the way they do, but I thought it would be instructive to poll some of my hiking friends as to what they thought. Boy, did I get an virtual earful. Clearly, many of my hiking associates have noticed the same thing. And trying to distill 10 - 15 pages of opinion, experiences, and observations ain't easy, but here goes. Most of the opinions as to why people don't carry maps with them seem to boil down into three categories. People either a) forget to take them; b) believe that they are sufficiently familiar with the proposed route that they don't really need to carry them; or c) are willing to cede decision making, route finding, etc to the outing leader and thus, don't want to bother carrying a map.

Let's

examine these concepts in more detail. Reason number one is pretty

straightforward. In the haste to get gear ready and leave the house at

the appointed time, it seems pretty easy simply to forget to take a

piece of gear with you. In the 500 or 600 backcountry outings I have

taken in the past 30 years or so, I must have forgotten to take a map

at least once or twice. Maybe. So let's just call this reason

"legitimate" and move on. Reasons Two and Three could be easily lumped

together, because they represent a willing disregard for both the

spirit and the letter of the rule of the Ten

Essentials. When people admitted to me that sometimes, they did

not deliberately carry a map, for one reason or another, I had to

sorta tease out of them what Paul Harvey would call "The REST of the

story."

Let's

examine these concepts in more detail. Reason number one is pretty

straightforward. In the haste to get gear ready and leave the house at

the appointed time, it seems pretty easy simply to forget to take a

piece of gear with you. In the 500 or 600 backcountry outings I have

taken in the past 30 years or so, I must have forgotten to take a map

at least once or twice. Maybe. So let's just call this reason

"legitimate" and move on. Reasons Two and Three could be easily lumped

together, because they represent a willing disregard for both the

spirit and the letter of the rule of the Ten

Essentials. When people admitted to me that sometimes, they did

not deliberately carry a map, for one reason or another, I had to

sorta tease out of them what Paul Harvey would call "The REST of the

story."

What seems to be left unsaid when, for example,

someone tells me that they feel like they know the route well enough,

is their perception of the difficulty or challenge of either putting

their hands on a topographical map of the area in which they will

hike, ski, bike, kayak etc. or carrying the map itself. I try to

understand these difficulties, but to me, they seem pretty minimal.

Yeah, you might have to spend a few minutes looking for a map in the

stack of 60 or 100 underneath your bed, which seems to be about the

only place sufficiently flat and large to store the classic USGS

quads. But is it really THAT hard?  Or maybe it is the weight of the maps? On a week long

backpacking trip, one can cross a LOT of 7.5 minute quads. Before the

days of digital maps, many of us would cut most of the borders off the

maps to save weight. And it was amazing how much those map borders

could add up on a long trip. But then on a long trip, when you get

deep into the backcountry, you really need the maps. And if something

goes wrong, you might even need more maps than you carried with you.

Other people might say: "Well, if I am going to a new area, to get the

topo map, I have to find a store that carries it, or order it

specially. That is not something I want to do for a day hike in an

area into which I don't expect to go frequently." Now it is true that

back in the days when USGS quads, printed by the government, and sold

in stores were the only option, getting maps could be a pain. But that

kind of argument, in this era of the Internet, is simply not credible.

(I will go into other sources of maps below.) But maybe what is not

being said is more interesting. A full answer from the person saying

that they know the route well enough might really go something like

this:

Or maybe it is the weight of the maps? On a week long

backpacking trip, one can cross a LOT of 7.5 minute quads. Before the

days of digital maps, many of us would cut most of the borders off the

maps to save weight. And it was amazing how much those map borders

could add up on a long trip. But then on a long trip, when you get

deep into the backcountry, you really need the maps. And if something

goes wrong, you might even need more maps than you carried with you.

Other people might say: "Well, if I am going to a new area, to get the

topo map, I have to find a store that carries it, or order it

specially. That is not something I want to do for a day hike in an

area into which I don't expect to go frequently." Now it is true that

back in the days when USGS quads, printed by the government, and sold

in stores were the only option, getting maps could be a pain. But that

kind of argument, in this era of the Internet, is simply not credible.

(I will go into other sources of maps below.) But maybe what is not

being said is more interesting. A full answer from the person saying

that they know the route well enough might really go something like

this:

I feel like I know the route so well, that when weighed against what I perceive to be a very small risk that something might happen in the backcountry where my knowledge of the route would be insufficient, the hassle of finding a map and/or its weight for carrying in my pack is simply too large.

Of course, we can argue about the risks of incidents occurring in the backcountry until we are blue in the face. Maybe a lot of people have never had anything untoward happen to them. Sorta like reaching the age of 85 and never having a broken bone. But the cold hard fact is that things can and do happen in the backcountry, and it ain't a question of IF, but WHEN. A simple scenario comes to mind: a bunch of folks are day hiking in the mountains on a one-way route. The hike is 12 miles long, involving maybe 2000 feet of climbing and 3000 feet of descent. The group has a vehicle parked at either end of the trail. The group has just crossed the high point and gets some distance below the pass, when one of the party severely sprains her ankle. My question for the person who claims to know the route well enough would be: Do you know the surroundings well enough, including short cuts, other trails, exactly where you are on the trail, the amount of descent, etc, so that with assistance, the gal with the sprained ankle can get out with the least amount of pain? If you are that aware of all the options - without a map, then you are a better man than I, Charlie Brown. Or maybe you've just hiked that trail too darn many times!

Let's examine

Reason Number Three: Ceding the decision making/route finding to the

leader. I think one of the reasons for the increase in popularity of

"guided" vs DIY trips has been the increase of intensity and duration

of the work schedules of many of us. The advent of the personal

desktop computer and the globalization of the work force surely

contributes. As many of the work force tries to do more and more with

less and less time, something that can buy one a bit more time is to

let someone else plan, guide, etc the backcountry trip. That goes for

everything from a day-long cross-country ski trip in the local

mountains or some guided day hiking in our National Parks, to a

two-week-long guided sea kayaking trip off the coast of Greenland.

Look, I appreciate the fact that it is nice to let someone else do the

heavy lifting. I was just enjoying such myself a few weeks ago.

Let's examine

Reason Number Three: Ceding the decision making/route finding to the

leader. I think one of the reasons for the increase in popularity of

"guided" vs DIY trips has been the increase of intensity and duration

of the work schedules of many of us. The advent of the personal

desktop computer and the globalization of the work force surely

contributes. As many of the work force tries to do more and more with

less and less time, something that can buy one a bit more time is to

let someone else plan, guide, etc the backcountry trip. That goes for

everything from a day-long cross-country ski trip in the local

mountains or some guided day hiking in our National Parks, to a

two-week-long guided sea kayaking trip off the coast of Greenland.

Look, I appreciate the fact that it is nice to let someone else do the

heavy lifting. I was just enjoying such myself a few weeks ago.

But, what happens if the leader becomes incapacitated, or worse, is incompetent?? Don't believe it? Well, here is a real life example: Sarah Boomer writes an interesting story about a guided, commercial raft down the Hulahula River on Alaska's North Slope. The water levels were high, and the group ended up "running the tundra" (rather than in the braided river bed) and ended up in the Arctic Ocean, several miles from where they wanted to be. Did they have a good idea of where they were? No. Did they have to paddle their rafts through the Arctic Ocean? You bet. When I first heard Sarah relate the story, my eyes just rolled. Sarah has her own take on things, but from my viewpoint, the word "incompetence" comes to mind. In these days of GPS units and digital maps (see below), to me, there is simply no excuse.

Now,

having been a leader on dozens of backcountry outings for clubs and

groups of friends, I appreciate the fact that everyone occasionally

exhibits what might be called "temporary incompetence." I recall

leading a Sierra Club group on one short day trip, off-trail in the

Great Smoky Mountains National Park. I "knew" the route, as I had been

over it many times before. But as anyone who has attempted to travel

off-trail for any distance in our country's most visited National

Park, the complexity of the terrain and density of the vegetation can

make off-trail traveling a challenging experience. Obviously, TOO

challenging for me that day. I missed a key early stream crossing, and

ended up in the wrong drainage. This resulted in even more

bushwhacking than I had intended, and a lot of head scratching on the

part of the group, as they realized that their leader had gotten a bit

confused. Yeah, we made it to the correct trail eventually, but not

without a few more banged shins, scratched faces, and a heap of

embarrassment for the leader.

Now,

having been a leader on dozens of backcountry outings for clubs and

groups of friends, I appreciate the fact that everyone occasionally

exhibits what might be called "temporary incompetence." I recall

leading a Sierra Club group on one short day trip, off-trail in the

Great Smoky Mountains National Park. I "knew" the route, as I had been

over it many times before. But as anyone who has attempted to travel

off-trail for any distance in our country's most visited National

Park, the complexity of the terrain and density of the vegetation can

make off-trail traveling a challenging experience. Obviously, TOO

challenging for me that day. I missed a key early stream crossing, and

ended up in the wrong drainage. This resulted in even more

bushwhacking than I had intended, and a lot of head scratching on the

part of the group, as they realized that their leader had gotten a bit

confused. Yeah, we made it to the correct trail eventually, but not

without a few more banged shins, scratched faces, and a heap of

embarrassment for the leader.

I guess the point to all this is that one needs to deliberately assess how much control or potential control of the situation one is willing to give up by not carrying one's own backcountry navigational equipment (map, compass, GPS, etc). Clearly, everyone will have a different comfort level here. For my comfort, I can not imagine being in the backcountry in ANY situation and completely ceding what ultimately might become my destiny to any leader, professional or otherwise. I recall taking a 10-day professionally guided raft trip on the lower 60% of the Grand Canyon. I opted for a guided trip, because I knew that, while I had done some whitewater canoeing, I really lacked the skills necessary to navigate the rapids on my own. However, you can be assured that I carried a complete set of USGS quads that covered the entire route. You never can tell: you hit the rapids wrong, a couple of rafts flip, one leader drowns, another is severely injured, and NOW, what do you do. It does not happen often, but it does happen. To the extent possible, I want to be in control of my own destiny. But maybe that's just me.

So far, these

reasons for not carrying navigational materials on a backcountry trip:

forgetting, feeling like one is sufficiently familiar with a given

route, or willingness to cede that responsibility to another person,

all made sense, but they simply did not add up, in my mind, to what I

perceive to be a relatively large number of "mapless" backcountry

travelers. Then I re-read a couple of comments sent to me by good

friends, one of whom is known for his "cutting through the crap" to

get to the heart of the matter. These are his words, not mine.

So far, these

reasons for not carrying navigational materials on a backcountry trip:

forgetting, feeling like one is sufficiently familiar with a given

route, or willingness to cede that responsibility to another person,

all made sense, but they simply did not add up, in my mind, to what I

perceive to be a relatively large number of "mapless" backcountry

travelers. Then I re-read a couple of comments sent to me by good

friends, one of whom is known for his "cutting through the crap" to

get to the heart of the matter. These are his words, not mine.

"The basic problem is that most folks do not know how to read a map, especially when a compass is needed to orient the map........ In the absence of the ability and experience most don't even try, instead relying on someone else to lead them. What good is bringing map if you cannot use it?"

Ah, here was the flash of light, the

epiphany. Perhaps one might call this the dirty

little secret of many backcountry travelers. It is hard to admit

illiteracy in any form. When I have given lectures on using the Ten

Essentials, one of which includes carrying a map, I often hold

up a highway map of entire state in one hand, and a USGS quad in

another, trying to make the point that the latter is vastly simpler

than the former. But perhaps, people find the highway map easier to

deal with because they a) have HAD to learn and b) there are actual

readable signs on highways that can be used to match with the road

numbers on the maps. I realize that one could argue that the terrain

features depicted on a topographic map is at least as good as a road

sign, and usually much larger. I don't know, maybe it is the contour

lines that confuse people. But I think the bottom line here is that if

you don't know how to read a topo map, LEARN. It is not hard. And

while there are good books out there to help you, you really don't

have to spend a dime. There are lots of web sites that explain such.

One hosted by Princeton University is a particularly good one.

And of course, it won't do you

any good just to look at the web site. Go out, get a topographic map,

and practice. Take one on your next outing. Keep it out, and look at

how the terrain depicted on the map compares with that which you see

around you. Practice can help a lot. Better yet, go out with someone

you know that does understand topographic map reading. Don't be afraid

to ask for a lesson. Most people love to give advice.

And of course, it won't do you

any good just to look at the web site. Go out, get a topographic map,

and practice. Take one on your next outing. Keep it out, and look at

how the terrain depicted on the map compares with that which you see

around you. Practice can help a lot. Better yet, go out with someone

you know that does understand topographic map reading. Don't be afraid

to ask for a lesson. Most people love to give advice.

Now, I have written up another report that goes into a lot of detail about the problems of a day hike turning into an overnight hike, when no one had a real map with them. But that incident occurred over three decades ago, and things have changed a lot since then. At least in the gear department. Perhaps two of the most important aids to the hiker that have been developed since that incident are inexpensive hand held global positioning receivers and digital mapping software. One huge benefit of digital mapping software is that it vastly improves the ease with which someone can get to a map to take on an outing. Simply put, it would seem that one is much more likely to carry a map if it is virtually no trouble to get your hands on one. Small, hand held GPS units complete the navigational package because they can tell you where you are, exactly, on the map.

The purpose of the rest of this article is to acquaint those backcountry travelers with digital maps and GPS that still may be unfamiliar with such. This section is not meant to be a tutorial, as you can find one elsewhere on this web site and as more extensive treatises elsewhere on the Internet. Note that if much of this sounds familiar, you must have read the latest edition of Cherokee National Forest Hiking Guide, as I have lifted most of this from a chapter in that book. Since I wrote the chapter, I don't mind plagiarizing myself.

Hand-held GPS units are essentially very sensitive radio receivers and timing devices. They take advantage of a constellation of 24-30 satellites lofted by the US military into earth orbits about 12,000 miles high over the past couple of decades. Without going into much detail, a small unit can take the signals from a minimum of four satellites and compute its position on the surface of the planet. (The units can make an estimate of position with only three satellite signals, but the quality of the estimate is vastly improved with the addition of one more signal.) The sensitivity of the units has improved dramatically over the past few years, to the point where a view to the sky unobstructed by vegetation is no longer required for a position fix. Theoretically, anyone with a detailed topographical map and a functioning GPS should be able to pinpoint his or her position on the planet to within a few meters. Never ever getting lost can be a powerful incentive for owning one of these units.

In the

aforementioned survey I did of hiking and climbing friends for this

article, one person mentioned that she did not consider GPS units to

be user friendly. Hmm, I first thought: What part about using a GPS is

not user friendly? You turn it on and it tells you where you are. What

could be simpler?? But then I thought: just like ownership of a set of

oil paints will not automatically make you a Michelangelo, owning a

GPS and a topo map will not do you a whole lot of good unless you know

how to use them. Like most things in life, at least a few skills are

needed. A GPS can tell you where you are, but you have to be able to

translate that information to a topo map. That means you have to have

some rudimentary knowledge of coordinate systems. Most self-propelled

backcountry travelers rely on Universal Transverse Mercator

coordinates. UTM coordinates tend to be easier to understand than

latitude and longitude, because the coordinates are in distances

(easier for most of us to digest) rather than degrees, minutes, and

seconds. UTM coordinates give a position in terms of the distance

north of the equator and east of the western boundary of the zone in

which an individual is hiking. Once you get the hang of it, you will

never want to go back to latitude and longitude. Almost all of the

topographical maps have UTM coordinates on them. You just need to

learn how to find and read them. There is a pretty good graphic on

such on slide 19 of

our GPS tutorial. That said, using the most basic functionality

of a GPS is pretty darn simple: you really do just turn it on, and it,

in a couple of minutes, reports your position. Vastly easier than

programming a VCR. Remember those??

In the

aforementioned survey I did of hiking and climbing friends for this

article, one person mentioned that she did not consider GPS units to

be user friendly. Hmm, I first thought: What part about using a GPS is

not user friendly? You turn it on and it tells you where you are. What

could be simpler?? But then I thought: just like ownership of a set of

oil paints will not automatically make you a Michelangelo, owning a

GPS and a topo map will not do you a whole lot of good unless you know

how to use them. Like most things in life, at least a few skills are

needed. A GPS can tell you where you are, but you have to be able to

translate that information to a topo map. That means you have to have

some rudimentary knowledge of coordinate systems. Most self-propelled

backcountry travelers rely on Universal Transverse Mercator

coordinates. UTM coordinates tend to be easier to understand than

latitude and longitude, because the coordinates are in distances

(easier for most of us to digest) rather than degrees, minutes, and

seconds. UTM coordinates give a position in terms of the distance

north of the equator and east of the western boundary of the zone in

which an individual is hiking. Once you get the hang of it, you will

never want to go back to latitude and longitude. Almost all of the

topographical maps have UTM coordinates on them. You just need to

learn how to find and read them. There is a pretty good graphic on

such on slide 19 of

our GPS tutorial. That said, using the most basic functionality

of a GPS is pretty darn simple: you really do just turn it on, and it,

in a couple of minutes, reports your position. Vastly easier than

programming a VCR. Remember those??

Some of the higher-end hand held GPS units have the capability to display electronic versions of simple topo maps on their screens along with the unit's position. This may be a handy feature and something with which to impress your friends, but somehow solely relying on a map, of which you can only see a few square inches at a time and has little detail, seems unsatisfying. The point of having a map is not only to provide a position, but also to provide context for that position. Four or five square inches of view just does not provide a lot of context. I think one reason for the popularity of the built-in maps is that the GPS can place your position on the screen's map, and thus, you really don't have to learn how to use either of the coordinate systems on real topographic maps.

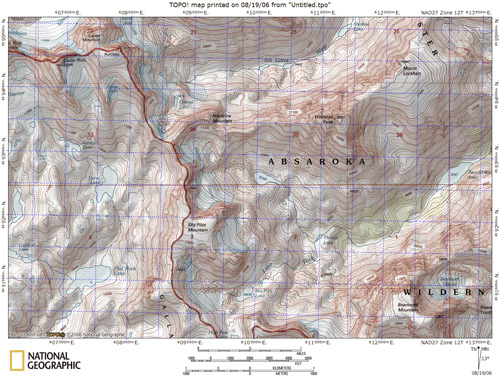

Clearly, with the

availability of powerful, low cost personal computers and color

printers, digital mapping products are becoming increasingly

competitive with that hiker's staple, the 7.5 minute quad topo. One

reason is simple economics. As of this writing, the cost of the

standard USGS topographical map is $8-$15. To cover just the southern

part of Tennessee's Cherokee National forest, it takes something like

27 topo maps. To cover just the western half of Montana's Gallatin

National forest, it takes 80 topo maps. However, you can currently

purchase a subscription service for $50 per year (www.AllTrails.com)

that give you access to border free maps of all the USA.

Alternatively, download as many USGS quads that you want for free at LibraMap.org

Sooo..., you do the math. Sure it costs some paper and ink to print

the maps, but the economics still support digital maps. Another

important feature is convenience. Have you ever planned to head for

the mountains on a Saturday morning, only to remember, after digging

through the pile of 50 or 60 quads you have stored so conveniently

under your bed, that the last time you hiked in the Citico Creek area,

your Whiteoak Flats topo got so soggy from the rain that you tossed

it? With digital maps, the solution is simple: just print yourself a

new map. Beats having to wait for the local backpacking shop to open

up with you hoping that they have not sold out of the map you need.

Clearly, with the

availability of powerful, low cost personal computers and color

printers, digital mapping products are becoming increasingly

competitive with that hiker's staple, the 7.5 minute quad topo. One

reason is simple economics. As of this writing, the cost of the

standard USGS topographical map is $8-$15. To cover just the southern

part of Tennessee's Cherokee National forest, it takes something like

27 topo maps. To cover just the western half of Montana's Gallatin

National forest, it takes 80 topo maps. However, you can currently

purchase a subscription service for $50 per year (www.AllTrails.com)

that give you access to border free maps of all the USA.

Alternatively, download as many USGS quads that you want for free at LibraMap.org

Sooo..., you do the math. Sure it costs some paper and ink to print

the maps, but the economics still support digital maps. Another

important feature is convenience. Have you ever planned to head for

the mountains on a Saturday morning, only to remember, after digging

through the pile of 50 or 60 quads you have stored so conveniently

under your bed, that the last time you hiked in the Citico Creek area,

your Whiteoak Flats topo got so soggy from the rain that you tossed

it? With digital maps, the solution is simple: just print yourself a

new map. Beats having to wait for the local backpacking shop to open

up with you hoping that they have not sold out of the map you need.

Another convenience of electronic/digital maps is the ability to customize, both the region of coverage and what features the map depicts. A running joke among hikers is that inevitably, a particular area of interest will always fall right at the junction of four topo maps. Since virtually all digital maps these days offer seamless viewing and printing, you just have to highlight the area you want to print, even if it is at the intersection of four maps, and print away.

But what if you are not ready to make the leap - or investment - of personally owned digital mapping software, or a subscription service? Well, there are certainly lower cost solutions than spending 40 cents a mile to drive to the nearest store that sells USGS quads for eight bucks a pop. "Free" is always a good price to pay, and for many areas, you can find free downloadable USGS maps. Essentially, these are digitally scanned topographic maps, called Digital Raster Graphics. DRG's can be found for many states. Just do a search for a particular state's Geographic Information System (GIS) data web site. Drill down until you find the DRG's, and download away. For example, here are pages for: Washington State, California, and Utah. just to give a few examples. Yes, it is true that you might need to know how to process zip files, and Tiff files, but such is easy to learn as well.

If you do a web search, and can not find downloadable DRGs for the area you are looking for, you can always buy a few DRGs from places like the USGS Store. The cost is nominal, and it beats having to drive somewhere to buy a map.

If you just need a small area covered someplace in the Lower 48 States, you might want to consider TopoQuest. This is a great site (there are several links on our web pages to one of their interactive maps). Another great site is CalTopo. Basically, just pick out a place you are interested in, drill down, and start printing. I have a friend who went on a multi-day backpacking trip in Owl and Fish Creek Canyons in Utah, armed only with maps he had printed off the web from such a site.

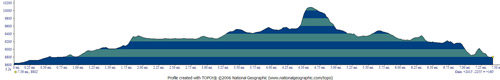

Not surprisingly,

however, digital mapping software packages or the subscription

services provide features that are simply not possible with paper

maps. For example you can trace the route you want to hike on the map,

and immediately generate an elevation profile of your route. That way,

there are no surprises when you get to that steep stretch of trail

that gains 1,400 feet in less than a mile. Even better, most modern

software permits the integration of your hand held GPS unit through a

USB cable connected to your computer. This will permit you to identify

and name key waypoints on your digital map and upload them to your GPS

unit, vastly easier than entering them by hand directly on your GPS

unit. Alternatively, you can turn on the tracking feature of your GPS,

throw it in the very top of your pack or wear it on your wrist, and it

will keep an exact record of where you hiked, skied, climbed, etc.

This feature is particularly useful for trail mapping (we have used

such for mapping some trails, and found that some existing maps had

significant mistakes as to trail locations) and for figuring out where

you actually went on your backcountry ski. Like all technological

approaches to addressing issues, there can be a few challenges. For

example, using digital maps requires spending a few minutes

understanding the differences among coordinate grids. Most paper USGS

quads use the NAD27 (North American Datum 1927) grid, but many digital

maps are set to default to the NAD 83 grid. (If you don't think this

should make much difference, see

here. And, of this writing, some hand held GPS units do not come

bundled with interface cables for personal computers. You have to

purchase them separately, and that requires a basic knowledge of how

to connect the two. It used to be that most commercial hand held units

connected to a PC through the "old fashioned"--and slow--serial port.

But the latter went the way of the 3.5" floppy disk. Now, most GPS

unites connect through a USB cable. You may have to learn a bit about

drivers for your GPS unit, but like they say, always RTFM!!

Not surprisingly,

however, digital mapping software packages or the subscription

services provide features that are simply not possible with paper

maps. For example you can trace the route you want to hike on the map,

and immediately generate an elevation profile of your route. That way,

there are no surprises when you get to that steep stretch of trail

that gains 1,400 feet in less than a mile. Even better, most modern

software permits the integration of your hand held GPS unit through a

USB cable connected to your computer. This will permit you to identify

and name key waypoints on your digital map and upload them to your GPS

unit, vastly easier than entering them by hand directly on your GPS

unit. Alternatively, you can turn on the tracking feature of your GPS,

throw it in the very top of your pack or wear it on your wrist, and it

will keep an exact record of where you hiked, skied, climbed, etc.

This feature is particularly useful for trail mapping (we have used

such for mapping some trails, and found that some existing maps had

significant mistakes as to trail locations) and for figuring out where

you actually went on your backcountry ski. Like all technological

approaches to addressing issues, there can be a few challenges. For

example, using digital maps requires spending a few minutes

understanding the differences among coordinate grids. Most paper USGS

quads use the NAD27 (North American Datum 1927) grid, but many digital

maps are set to default to the NAD 83 grid. (If you don't think this

should make much difference, see

here. And, of this writing, some hand held GPS units do not come

bundled with interface cables for personal computers. You have to

purchase them separately, and that requires a basic knowledge of how

to connect the two. It used to be that most commercial hand held units

connected to a PC through the "old fashioned"--and slow--serial port.

But the latter went the way of the 3.5" floppy disk. Now, most GPS

unites connect through a USB cable. You may have to learn a bit about

drivers for your GPS unit, but like they say, always RTFM!!

Probably the most significant current limitation with hand held GPS units is potential positional error. Despite vast improvements in sensitivity and the shift to simultaneous multi-satellite reception in the past few years, even the best units will occasionally place you in the middle of that lake over there, 400 meters to the west. Two of the biggest problems are signal scatter and signal bounce. The former is pretty easy to discern. In the rain, under a significant leaf canopy, your chances of getting an accurate fix may be limited. Your chances of getting any kind of a position fix are only slightly better. The wet leaves act as signal reflectors and it will appear as though the GPS simply cannot make up its mind as to where it is.

Perhaps more

insidious is the problem of signal bounce. That is, the signal from a

particular satellite will bounce off a cliff face or rock wall before

it reaches the GPS. This problem is usually minimized if you can pick

up signals from six or eight satellites at one time. But often in the

mountains, the terrain limits the view to the horizon and you may be

stuck with only four signals. You take a reading, more or less to

confirm where you think you are, and the GPS places you several

hundred meters away in a spot that simply does not make sense, based

on what you can see around you. If this happens, or if the reading you

get is a bit suspicious, walk 30 to 50 meters away from your original

spot, and take another reading. I was once near the confluence of two

major creeks in the GSMNP. I knew exactly where I was, but I pulled

out my GPS anyway. I got a reading that did not make any sense. I

looked around me, and there was a big rock face up on the hill behind

me. I moved about 20 meters, and watched as the GPS corrected its

position. This does not happen frequently, but it does happen, so pay

attention to the surrounding landscape while you are getting your

position fix. (A lot of this is covered with illustrations in our GPS tutorial.)

I have not done any comparative tests, to determine if my WAAS-enabled

(Wide Area Augmentation System) GPS is any less susceptible to the

signal bounce problem than my non-WAAS enabled GPS unit. There is a good concise

explanation of how WAAS works at the Garmin web site, but

essentially, if you have a clear view to the sky, your inexpensive

hand held WAAS-enabled GPS can locate your position on the planet to

within 10 feet or so. I am not sure I really need to know if I am

standing on the north or south side of a small spring - I can usually

figure that out myself. Of course, WAAS was developed for assisting

with commercial air traffic landings, and in that case, plus or minus

ten feet can make a big difference.

Perhaps more

insidious is the problem of signal bounce. That is, the signal from a

particular satellite will bounce off a cliff face or rock wall before

it reaches the GPS. This problem is usually minimized if you can pick

up signals from six or eight satellites at one time. But often in the

mountains, the terrain limits the view to the horizon and you may be

stuck with only four signals. You take a reading, more or less to

confirm where you think you are, and the GPS places you several

hundred meters away in a spot that simply does not make sense, based

on what you can see around you. If this happens, or if the reading you

get is a bit suspicious, walk 30 to 50 meters away from your original

spot, and take another reading. I was once near the confluence of two

major creeks in the GSMNP. I knew exactly where I was, but I pulled

out my GPS anyway. I got a reading that did not make any sense. I

looked around me, and there was a big rock face up on the hill behind

me. I moved about 20 meters, and watched as the GPS corrected its

position. This does not happen frequently, but it does happen, so pay

attention to the surrounding landscape while you are getting your

position fix. (A lot of this is covered with illustrations in our GPS tutorial.)

I have not done any comparative tests, to determine if my WAAS-enabled

(Wide Area Augmentation System) GPS is any less susceptible to the

signal bounce problem than my non-WAAS enabled GPS unit. There is a good concise

explanation of how WAAS works at the Garmin web site, but

essentially, if you have a clear view to the sky, your inexpensive

hand held WAAS-enabled GPS can locate your position on the planet to

within 10 feet or so. I am not sure I really need to know if I am

standing on the north or south side of a small spring - I can usually

figure that out myself. Of course, WAAS was developed for assisting

with commercial air traffic landings, and in that case, plus or minus

ten feet can make a big difference.

When all is said and done, the phenomenon of positional errors is a good reminder. All the fancy hardware is not a substitute for good map reading skills when you go into the wilderness. It is sometimes too easy to rely on technology, only to learn too late that you did not really know how to use it, or the batteries were about to run down. Enjoy the technological advances, but do not forget or ignore the basics. And carry spare batteries - AND a map.

© Roger A. Jenkins, 2003, 2006, 2015, 2018; Photos of Roger,and George and Roger in woods with GPS © Suzanne A. McDonald, 2001, 2006; Photo of splinted leg © Andrew P. Butler, 2002, 2006