Lost in Raven Fork

Day 2

The party of two spent the night huddling together on a sandbar in the middle of the creek, where, of course the cold air settles at night. One of the two women in the party of two shivered uncontrollably for several hours. They both were so cold when morning arrived that they could not move until the sun finally struck their sandbar at 10 am on Sunday. As it turns out, they were probably well within a mile of the group from which they'd split off. The two women proceeded downstream, reaching the point where Raven Fork intersects the Enloe Creek trail within an hour or so. There, they met a ranger (who'd been notified to be on the lookout for them by the leader's wife), and told him about the other party of five. The women made it back to the trailhead on Straight Fork Road sometime after noon on Sunday.

The party of five (4 men and one woman) had a more difficult time. The group of five spent the night huddled together under a rock overhang above the creek. They ripped apart the two plastic rain ponchos they had and tried to wrap the group with them. While coverage was not 100%, it helped. The woman replaced her jeans, now feeling like sheets of ice, with a pair of thin hiking shorts. While flirting with hypothermia all night, they were thankful that the weather was clear. However, the clear skies contributed to radiational cooling of the atmosphere, which exacerbated their situation.

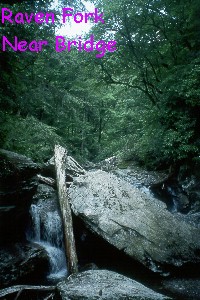

To paraphrase the leader, the mind can play funny tricks on you when you're cold and exhausted. The group somehow convinced themselves during the night that they were downstream of the junction with the Enloe Creek trail (not realizing that since the leader had last scouted the hike six years ago, a bridge had been built across Raven Fork near Campsite #47, and thus, it would have been hard to walk under the bridge without noticing it The bridge was put in after a hiker, attempting to ford rain-swollen Raven Fork, was washed away to his death a few summers before.). So, at 6:30 am, the group headed east-north east, away from the creek, up a steep ridge, thinking that it must be the southwestern end of Hyatt Ridge. If they were correct, they would top out on the ridge, head north, and eventually run into the Enloe Creek Trail near Low Gap. Unfortunately, they were still upstream of the bridge, so they merely expended a tremendous amount of energy climbing a spur of Breakneck Ridge. When they topped out and headed north, they could find no trail, and descended into a creek valley to their east. It had taken them over four hours to make this climb, and one hour to do the descent to the floor of a creek valley. The woman in the party of five was getting her legs torn up from greenbriers and brambles, but putting on the wet jeans did not seem much more appealing. (It should be noted here that, had they continued but a few hundred yards to the north from their high point, they would likely have intersected the trail which they had taken from McGhee Springs down Breakneck Ridge. Such speaks to the extreme difficulty navigating when one is hiking off trail, once you loose your point of reference. In an area of complex topography, it is very difficult to tell exactly where you are. It is tough to see long distances to get compass sightings to make a triangular fix. The group also had no altimeter with them, and this was in the days before cheap hand held GPS units.)

This valley turned out to be Jones Creek, which flows back into Raven Fork, about a half a mile downstream of where they had started their climb several hours previously. The group was staring to spread out again, as differences in physical stamina began to show. Becoming concerned that they might have to spend another night in the wilderness, they proceeded downstream as fast as their exhaustion would permit. Around 1 pm, they got back down to Raven Fork. One of the group would later report that very dark thoughts were being discussed, as individual fears of their ability to survive another night out began to surface. At 2:15 pm Sunday, the group was spotted by a helicopter which had been alerted by the ranger as to their plight. Spirits soared. At about 3:15 pm, they reached the point at which Raven Fork flows under the new bridge, and at 6 pm, they were at the trailhead, exhausted and beat up, but otherwise OK.

This valley turned out to be Jones Creek, which flows back into Raven Fork, about a half a mile downstream of where they had started their climb several hours previously. The group was staring to spread out again, as differences in physical stamina began to show. Becoming concerned that they might have to spend another night in the wilderness, they proceeded downstream as fast as their exhaustion would permit. Around 1 pm, they got back down to Raven Fork. One of the group would later report that very dark thoughts were being discussed, as individual fears of their ability to survive another night out began to surface. At 2:15 pm Sunday, the group was spotted by a helicopter which had been alerted by the ranger as to their plight. Spirits soared. At about 3:15 pm, they reached the point at which Raven Fork flows under the new bridge, and at 6 pm, they were at the trailhead, exhausted and beat up, but otherwise OK.

It is clear that this situation could have been averted, or at least mitigated, if some crucial mistakes had not been made. These mistakes have taught everyone some lessons.

1. Know your route. The more difficult the trip, the more critical this is. It's ok to lead an unscouted hike, but advertize it as such. Once every six years is probably not enough to scout a cross-country hike. I feel somewhat responsible in that I assumed that the leader had scouted the trip more recently than he had. The trip was difficult for me 3 years ago, and I assumed he knew it would be as tough as it apparently was. (A corollary is to make reasonable assessments about the length of time required to do the hike. The loop that the group was taking is a bit over 13 miles long. Given that half of the outing was off trail, it is probably unreasonable to think that a group of five with diverse physical skills and stamina would likely complete the hike in less than 12 hours. It took George and I about 13, under somewhat lower stream flow conditions. If you depart the trailhead at 10:15 am, .... well, as they say, do the math.)

2. Screen your participants well. Make sure their ability and attitude are commensurate with the planned hike. I've had people who wanted to come on the Roan Mtn backpack (the traverse between Carver's Gap and US 19E along the Appalachian trail, usually done in late June) and sleep under the stars. I had to tell them either to take shelter or don't come, since it usually rains on us and gets cold. I'm sure that many of us have lead hikes where one or more of the individuals were really not up to the task, and because of that the entire group was inconvenienced. Keep that in mind. Don't be afraid to ask a few questions of someone whose skills you don't know.

3. TAKE THE "TEN ESSENTIALS"! ALWAYS. WITHOUT FAIL! NO EXCUSES! I don't know how many times I've had people laugh at me for taking a flashlight on a day hike. A couple of folks who don't laugh at me are the Sierra Clubbers from Nashville, who went on an easy (I mean, like, real easy) hike in Pickett State Park, missed a trail sign, kept going, got confused, turned around, and were bedding down in a pile of leaves for a very cold night when we found them. Not having something with which to start a fire is absolutely inexcusable. Not just for the leader, but for every person on the hike. Make sure that your folks have these essentials. A wool or PolarTek hat is important because you lose so much heat from your head. The leader should always have a topo map covering the area in which the group is hiking. While a topo map may not have been as useful on this hike as on some others, incoming stream patterns could have given a clue as to location. A good topo map, altimeter, and compass is an awesome sombination for cross country in the Smokies. But altimeters are expensive (Note that they used to be, but now, the type that are built into wrist watches are both accurate and reasonably priced), and a compass and map can still tell you a lot.

4. Know when to turn back. It's hard to admit defeat, but the wilderness, only if it's a sudden snow squall in May, can be a tough opponent. [If you think snow in May is impossible, you've forgotten Memorial Day weekend, 1979. I started a hike from Paul's Gap with 5 inches of snow on the ground.] Had this group turned around when it became apparent that they were not moving down creek very fast, they would not have had to spend the night out.

5. When you get in trouble, do not allow the group to fragment. The woman who spent the first few hours of the night shivering uncontrollably had started the long descent into terminal hypothermia. She was lucky. She pulled out. Think what would have happened if it had rained that night. There is safety, and warmth, in numbers. If one of the party of two had hurt themselves trying to rockhop in the dark, the situation would have been desparate, and rescue with one person extremely difficult.

Looking back on this, 13 years later, some of what transpired on this trip seems nearly unbelievable, but then, so does my having hiked to the wrong damn col in Olympic National Park back in 1990. We all make mistakes. The primary issue seems to be: what prior precautions have been taken to insure that big mistakes do not convert a bad situation into one which is catastrophic. Being prepared when you start hike seems fundamental to preventing the long skid down that slippery slope.

Epilogue

We are something like 19 years past the time of the hike, and I have recently had the opportunity to review the entire affair with the leader, a fellow whom I have considered as a friend for over 25 years. Dan has led dozens and dozens of private and group outings, and been in many situations where leadership skills were required for the successful and safe completion of those outings. Challenging situations that he handled with grace and ease. So what went wrong back in Raven Fork? That was the subject of a number of email exchanges over the past few months. I want to distill that "conversation" into its most pertinent parts, because I believe it has at least one key lesson for all of us who find ourselves, de facto or otherwise, in leadership roles in the wilderness. (And I have permission to quote him in his more elegant passages.)

Dan, the leader of that trip, observed after reading the web write up, that he believed he was under such severe emotional duress, because of many things going on in his personal life (the kind of crap that no human being should HAVE to deal with), that he simply had no business in trying to lead a trip to the corner McDonald's, let alone a challenging off-trail wilderness hike.

It took me a while to appreciate the severity of what he was describing, and I wrote him back the following (edited for improved clarity):

"While I agree, in retrospect, that you should probably not have been leading an outing, especially if you had so many other things on your mind, I would draw this analogy to help you understand from whence I was coming:

There are certain rules that one always follows. For example, when you are driving and come to a stop sign, you stop. You stop whether you just broke up with your girlfriend, just murdered someone, or just dropped your cell phone in your lap. Why, because the consequences of not doing so are so bad that you have it burned into your brain to STOP. I liken the points I bring up at the end of the 1987 memo similar to always stopping at a stop sign. The concept is that if you follow them, then it does not make any difference if you are suffering from a hangnail or clinical depression, or something in between. You have a safety pad."

Dan, much more eloquent than I, offered: "Stop signs, shit, there should have been flashing strobe lights. ......... To see the stop sign you have to know you're on the friggin' street!"

Dan makes an excellent point, and as I used to say about a particularly challenging time in my own life, if you heap enough stress on a person, and force them to make decisions, they will ultimately make some bad decisions. But I think Dan summed up the situation much more effectively.

"People under significant stress should not lead trips. The Catch-22 is, when you're under significant stress, you can no longer evaluate it's total effects. Assume you're mental, emotional and even physical abilities have been curtailed, even though you might not think they are. Assume the worst; don't lead trips. There is nothing to feel guilty about in admitting such a thing. A tiny twinge of guilt or embarrassment, or frustration at not being able to confidently do what you normally can, none of this is worth risking other people's safety. It's that simple.

The "11th Essential" is what's going on inside you, the potential leader. If you've just lost a loved one, or you're going through a divorce, or you've lost a job or career, you probably shouldn't be leading a trip. Until the smoke clears, relax; go on someone else's trips. This "11th Essential" is a slate-clearing deal-breaker; if you violate it, it's possible to get someone seriously injured or killed even if every person on the trip has the "ten essentials."

So, to me, it seems clear that this incident, and the run up to and fallout from it, has many lessons to it. But first and foremost, whether you are leading your kids on a stroll in the Smokies, or leading a group of independent backpackers on a challenging off-trail route in the Beartooths of Montana, or the canyons of SE Utah, you as a leader must always be willing to take a hard look at where you are psychologically, and whether you are up to assuming the role of leader. If you are not, it is better to step aside rather that potentially compromise the lives and/or well being of those who have put their trust in you.

Roger Jenkins, Bozeman, MT, May 2006

Back to Day 1

© Roger A. Jenkins, 1987, 2000, 2006